3 MIN READ

Aflatoxin in Corn

July 29, 2020

Get Year-Round Updates From Our Agronomic Experts

Aflatoxin is a toxic substance produced by the fungi Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus parasiticus in agricultural crops such as corn kernels, cotton seeds, and tree nuts. Aflatoxin in corn must be monitored closely as it is highly toxic to many animals and can be fatal to livestock. Aflatoxin can infect corn across the Midwest and Southern United States, especially if corn is under insect or drought stress. Identifying the fungus that produces aflatoxin, testing grain for contamination, and managing contaminated grain can help control aflatoxin in corn.

Development of Aflatoxin

Aspergillus flavus and A. parasiticus fungi can infect corn kernels in the field and during storage. The fungi can be recognized by a yellow-green (A. flavus) or green-gray (A. parasiticus) mold on the corn kernels (Figure 1).1

The fungi overwinter on plant residue and produce abundant spores in favorable conditions. Moisture is required for sporulation. The fungal spores land on silks and kernels by wind dispersal. Under favorable environmental and crop conditions, the spores begin to grow. Wounds from insect feeding also create favorable growth sites.

Hot, dry days and warm nights coupled with moisture content levels of 17-30% are favorable for the development of Aspergillus ear rot on kernels. When corn is stressed, the fungi can initiate aflatoxin production on infected kernels of susceptible products. The most common stresses that lead to aflatoxin production in the field include excessive heat and drought conditions. In the Southern United States, higher insect populations and air temperatures can increase the incidence of Aspergillus ear rot and aflatoxin production. Drought conditions coupled with high humidity or high nighttime temperatures can also lead to sporadic outbreaks. Poor grain conditioning and storage conditions, such as insufficient drying, can lead to post-harvest Aspergillus infection and aflatoxin production on infected kernels.

Aflatoxin sampling and testing procedure

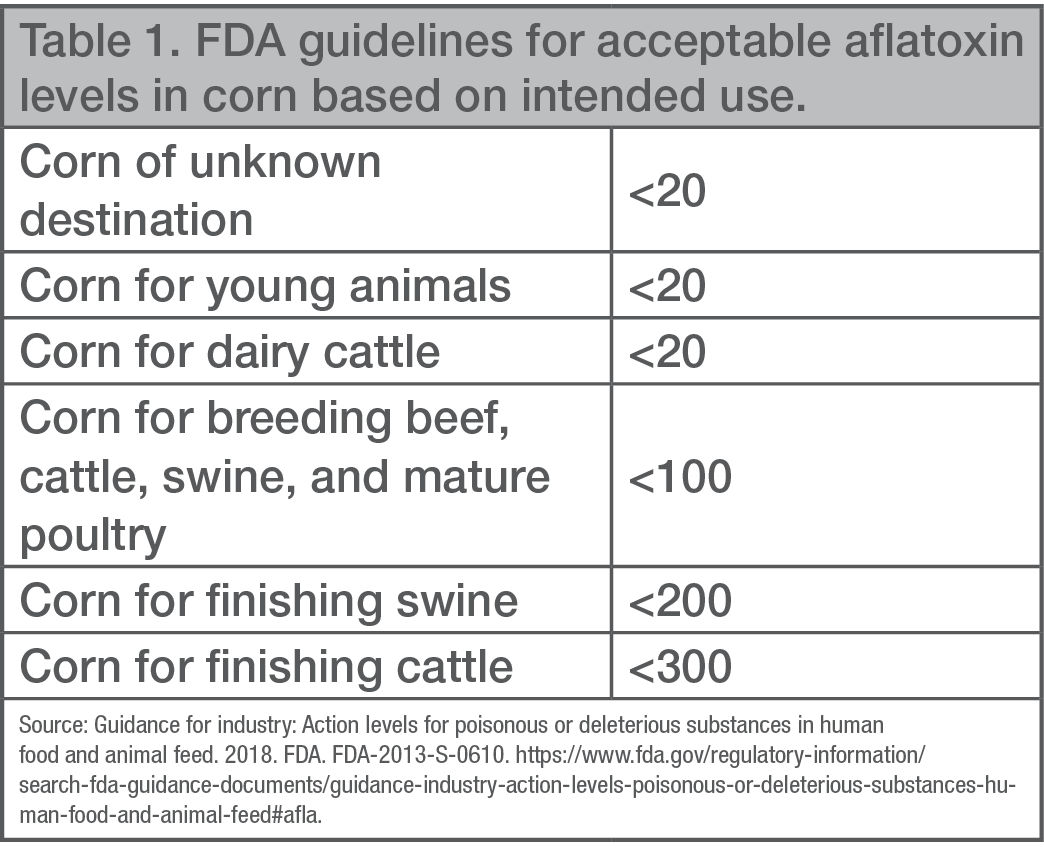

Aflatoxin does not occur uniformly in bulk corn, so samples should be taken in several areas of a load or storage bin. Contact your local grain testing laboratory for specific sampling and handling instructions. A chemical test can be performed at a certified laboratory to detect and quantify potential aflatoxin accumulation in a sample. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) had developed guidelines for acceptable aflatoxin levels based on intended use (Table 1).2 A black light test can be used only to detect the presence of Aspergillus spp., but not aflatoxin itself.2 Since not all strains of Aspergillus produce aflatoxins, black light test results should not be accepted as grounds for rejection of corn.

Aflatoxin Management

Corn product selection is an important step in aflatoxin management. Products with larger, tighter fitting husks, insect resistance traits, and drought tolerance can help reduce the potential risk of aflatoxin. Other factors that may have an influence on aflatoxin production are flowering time and days to maturity. Consider the following tips for reducing aflatoxin in corn:Select corn products that are well-adapted to local growing conditions.

Control ear-damaging insects by planting corn products that provide protection against insects. Reduced insect damage can help lower the potential for Aspergillus infection.

Scout fields at black layer and two weeks prior to harvest for Aspergillus infection and insect damage.

Develop a plan to test grain for aflatoxin contamination. Grain with high infection levels should be segregated from non-contaminated grain.

Harvest fields with ear rot or insect damage as early as possible. The longer infected ears remain in the fields, the greater the opportunity for aflatoxin accumulation.

Adjust combines according to the owner’s manual to reduce kernel damage. Open sieves and increase fan speed to help remove damaged or lightweight kernels.

Wet corn should be dried immediately to moisture content levels of 12.5 to 13%.3 Grain should then be cooled quickly. Drying equipment should be set to minimize kernel cracking and other damage.

Routinely monitor storage bins for issues such as crusts, hot spots, and mold.

Thoroughly clean storage bins and handling equipment to help prevent contamination. Refer to the owner’s manual for specific guidelines.

Handling Contaminated Grains

There are options available to growers with contaminated grain. Affected grain cannot cross state lines and will likely have a discounted price. Grain that is contaminated with aflatoxin at levels below 300 ppb (parts per billion) can be fed to local beef cattle.3, 5 Another alternative for contaminated grain may be ethanol production. Aflatoxin does not accumulate in the ethanol but can be concentrated in the dried distiller’s grains (DDGs). Some ethanol plants may not accept contaminated grain because they would not be able to sell the DDGs as animal feed. Cleaning the grain can be done with a screen or gravity table. Feed additives, such as beta-glucans, may reduce the toxicity of aflatoxin by reducing absorption in the animal. Reduced intestinal absorption results in less exposure to the animal and less transfer to milk in ruminants.

Sources

1 Herrman, G.T. and Trigo-Stockli, D. 2002. Mycotoxins in feed grains and ingredients. Kansas State University. https://www.plantpath.k-state.edu/extension/.

2 Guidance for industry: Action levels for poisonous or deleterious substances in human food and animal feed. 2018. FDA. FDA-2013-S-0610. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/guidance-industry-action-levels-poisonous-or-deleterious-substances-human-food-and-animal-feed#afla.

3 Worly, J., Sumner, P.E., and Lee, D. 2017. Reducing aflatoxin in corn during harvest and storage. UGA Cooperative Extension Bulletin 1231. https://extension.uga.edu/publications/detail.html?number=B1231&title=Reducing%20Aflatoxin%20in%20Corn%20During%20Harvest%20and%20Storage

4 Munkvold, G., Hurburgh Jr., C.R., Loy, D., and Robertson, A. 2012. Aflatoxins in corn. Iowa State University Extension. Publication Number PM 1800. https://store.extension.iastate.edu/product/Aflatoxins-in-Corn.

5 Kenkel, P., and Anderson, K. 2019. Grain handlers guide to aflatoxin. Cooperative Extension, USDA, National Institute of Food and Agriculture. https://cooperatives.extension.org/grain-handlers-guide-to-aflatoxin/

7002_S3

Disclaimer

Always read and follow pesticide label directions, insect resistance management requirements (where applicable), and grain marketing and all other stewardship practices.