7 MIN READ

Anthracnose Diseases in Corn

August 17, 2023

Anthracnose can cause leaf blight, top dieback, and stalk rot. However, corn infected with leaf blight does not necessarily progress to top dieback or stalk rot, because resistance to the stalk rot phase of anthracnose diseases is not highly related to resistance to the leaf blight stage.

Disease Development

Anthracnose is caused by the fungus Colletotirchum graminicola, which overwinters on corn residue. Spores spread to growing plants via windblown rain and rain splash. Infection is favored by increased periods of low light intensity (overcast conditions) and high humidity with moderate temperatures.

Anthracnose can infect corn at any point in the growing season. The leaf blight phase is most common early in the season, when temperatures are moderate and conditions are wet. However, it can also occur late in the season on leaves in the upper canopy. The fungus can infect roots from the soil, or rain and wind can disperse fungal spores from plant residues to corn stalks. Anthracnose stalk rot is the most common stalk rot in the Eastern Corn Belt. Top dieback—a condition that causes stalk death above the ear—is a form of the stalk rot phase that usually occurs four to six weeks after pollination.

Different Phases of Anthracnose

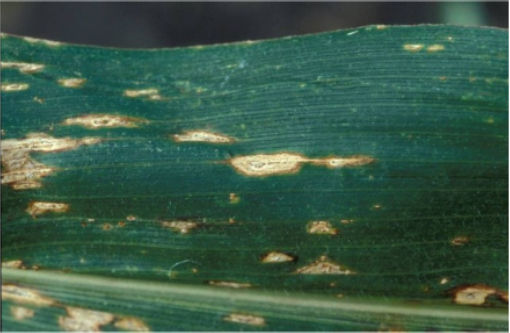

Leaf Blight Phase — Lesions are nondescript, oval to spindle-shaped necrotic areas that may appear water soaked or chlorotic. Lesions are often found on the bottom leaves first and can progress to the upper leaves. Small, black, hair-like fungal structures called setae often occur in necrotic tissues and can be seen with the help of a hand lens. Lesions are often tan to brown with yellow to reddish-brown borders (Figure 1). Heavily infected leaves wither and die. This phase of the disease is rarely an economic concern. It is most common in fields in which corn was planted the previous year and can occur both early in the season and late in the season, though it rarely occurs mid-season.

Top Dieback — In fields with heavy anthracnose stalk rot pressure, it is common for a portion of the plant above the ears to die prematurely while the lower plant remains green. This symptom, known as “top dieback,” may appear as early as one to three weeks after tasseling (Figure 2)1.

As the stalk rot phase progresses the pith and the vascular system decay, reducing water translocation to the top leaves. In cases where water availability is reduced in the soil, the top leaves tend to dry down and die because of the reduced water supply. However, caution is needed when diagnosing anthracnose infections, as this symptom can also be the result of natural dry down or insect injury. Anthracnose infection can be confirmed by removing the top leaf sheaths. If removing the sheaths reveals that the stalk has black spots or streaks that can not be removed with a fingernail, the plant is likely infected.

Stalk Rot Phase — Disease onset usually occurs just before plants mature (Figure 3). Typically, the entire plant dies in the stalk rot phase and several nodes have already rotted. Late in the season, after plants show signs of early death, a shiny, black discoloration develops in blotches or streaks on the stalk surface, particularly on lower internodes (Figure 4). Internal stalk tissue also may become discolored and soft, starting at the nodes.

Stalks may also have discolored pith while the rind remains green. Lodging typically occurs higher on the stalk than with other stalk rots.2

Management Options

Prior to Harvest — Plants that are severely damaged by the stalk rot phase may become lodged prior to the normal harvest period. Therefore, preparations should be taken to harvest problem fields early. Although high grain drying costs may be a concern when harvesting wet grain, this expense may be a better option than the potential loss of yield due to increased lodging later in harvest. Scouting for stalk rots should be done 40 to 50 days after pollination and before the black layer develops. Healthy stalks should be firm, and soft stalks may be diseased. Two methods are used to scout for stalk rots:

- The push test— Randomly select 20 plants from five different areas of the field for a total of 100 plants. Push the top portion of the plant 6 to 8 inches (15 to 20 cm) from the vertical to 45° and note whether or not the plant lodged.

- The pinch test or squeeze test— Randomly select 20 plants from five different areas of the field for a total of 100 plants. Remove lower leaves and pinch or squeeze the stalks above the brace roots. Record the number of rolled stalks.

Regardless of which test is used, if more than 10 to 15 percent of stalks are observed have the disease and weakened stalks at 40 to 60 days after pollination, harvesting should occur as quickly as possible.

Next Season —

Tillage — Burying infected residue can help decrease the amount of disease inoculum.

Crop Rotation — Planting a non-host crop such as soybean can help reduce inoculum. In fields with a severe anthracnose problem, a two-year rotation away from corn may be considered.4

Product Selection — Select corn products rated well for tolerance to anthracnose. Corn products may have ratings of tolerance to either the leaf blight phase or the stalk rot phase of anthracnose, or to both phases. Tolerance to one phase does not indicate that the product has tolerance to the other phases. Ask your seed supplier for locally adapted products that have good tolerance ratings.

Minimize Stress and Cannibalization — Stalk rots can become more prevalent as a corn crop endures additional stress. Stresses such as foliar diseases, insect damage, and drought can increase the risk of stalk cannibalization, which can in turn increase the risk of lodging.

Fertility — Stalk rots can be more common and severe in fields with key nutrient imbalances, low fertility levels, or low soil pH. Plants grown in fields with an imbalance between nitrogen and potassium are very susceptible to stalk rots.

Sources

1Stack, J. and Jackson-Ziems, T. Anthracnose. University of Nebraska-Lincoln. https://cropwatch.unl.edu/plantdisease/corn/anthracnose

22019. Anthracnose stalk rot of corn. Crop Protection Network. https://cropprotectionnetwork.org/encyclopedia/anthracnose-stalk-rot-of-corn.

3 Brown, C., Follings, J., Moran, M., and Rosser, B. (Eds.) 2023. Agronomy guide for field crops. Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food, and Rural Affairs. Pub 811. https://www.ontario.ca/page/agronomy-guide-field-crops

4Lipps, P.E. and Mills, D.R. Anthracnose leaf blight and stalk rot of corn. Ohio State University Extension. AC-0022-01. https://www.knowmoregrowmore.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/0022.html

1211_132602

Disclaimer

Always read and follow pesticide label directions, insect resistance management requirements (where applicable), and grain marketing and all other stewardship practices.