3 MIN READ

Corn Grain Fill During Drought Stress

August 25, 2025

The yield potential of corn is perhaps most at risk to drought and heat stress during pollination and grain fill. In many situations, drought stress is compounded by heat stress as these two components commonly occur simultaneously.

Evapotranspiration and Daily Water Use by Corn

Evapotranspiration (ET) is the combined loss of water from the soil through evaporation and water used by a plant during transpiration. As the corn plant grows and leaf area increases, transpiration becomes the primary mechanism for water loss. Evapotranspiration rates are estimated to range from about 0.06 inches per day for 4-leaf corn (V4 growth stage, counted as leaf collars) up to 0.33 inches per day during the V16 through blister (R2) growth stages. Stress is induced when ET rates exceed the soil’s capacity to supply adequate water to the crop. Perhaps the most common and noticeable symptom of water stress in corn is leaf rolling (Figure 1).1 This is a defense mechanism used by the corn plant to reduce the exposed leaf area, thereby reducing ET. If leaf rolling occurs during the hottest part of the day, and the leaves re-open with cooler temperatures, yield loss is likely to be minimal. However, if leaf rolling persists for more than 12 hours per day, yield may be negatively affected.2 Yield loss due to water stress is considered negligible up to the V12 growth stage.1

Pollination and Drought Stress

By the time pollination begins, the potential ear size on a corn plant has been determined. The number of kernel rows is set as early as the V6 to V7 growth stages, while the number of kernels per row (ear length) is developed over a longer period of time and is complete by the V15 to V16 growth stages.3

Drought impacts corn during pollination in two ways. The silks are mostly water; therefore, drought can reduce the silk’s growth rate and emergence from the ear tip. As previously mentioned, the leaves of water stressed corn usually curl which helps to reduce transpiration; however, the rate of photosynthesis may also be reduced. A reduction in photosynthetic rates lowers the amount of nutrients provided to the developing kernels. The amount of sugars available to the developing kernels during the week before and the week after pollination is critical in maintaining the kernel numbers. To maximize yield potential, it is of the utmost importance that silks are available during pollen shed.

Under severe drought stress, as evidenced by several days of leaf rolling, silk elongation can be severely reduced. Silking begins with the ovules at the butt end of the ear and moves up the ear as the process continues. Under drought conditions the silks may be delayed in emergence from the husk and miss the pollen (often referred to as “missing the nick”) or desiccate to the point where they are not receptive to pollination resulting in completely barren ears. If moisture alleviates drought conditions during pollination, some ears may be partially filled. Additionally, drought stress can accelerate pollen shed, especially with excessive heat, leading to increased potential for a lack of synchronization. Severe cases of accelerated pollen shed can be a result of a phenomenon known as “tassel blast.”

If the corn plant is under considerable drought stress with continual wilting for two weeks prior to silk emergence, yield potential can be reduced 3 to 4% per day. If the stress continues during silking and pollen shed, a yield reduction of 8% per day could occur. If the stress continues after silking for a two-week period, yield potential could be reduced up to 6%.4

Pollination and Heat Stress

Like drought, heat can dramatically impact silk and tassel synchrony. If silking is delayed, most of the pollen may have already been shed, particularly when heat is combined with water shortage. If the silks begin to desiccate, viability decreases, the pollen tube ceases to grow, and ovule fertilization doesn’t occur. This is particularly true if high temperatures occur when humidity is low.

Pollen production and viability can be reduced with daytime temperatures above 95 ˚F. Reduced kernel set can be the result of excessive heat during pollination, particularly in stress-prone areas of the field.

While excessive temperatures can reduce pollen production and viability, pollen shed usually occurs in the morning before temperatures become excessive. Additionally, pollen is produced over a period of about two weeks; hopefully allowing for temperatures to moderate. Heat stress alone doesn’t usually impact pollination negatively if soil moisture levels are adequate.4,5

How do I Know if Pollination was Successful?

A quick test that can be performed in the field to give an indication of how successful pollination was is called the “shake test.” Simply remove the husk and gently shake the ear. Silk that is attached to a fertilized ovule will fall off. If fertilization has not occurred, the silk remains attached (Figure 3). Another test can be performed about ten days post-pollination by examining developing kernels in the R2 growth stage that should appear to be a watery blister (Figure 4).

The Impact of Water and Heat Stress on Grain Fill (Kernel Development)

The ideal temperature range for corn is between 86 °F for daytime and 50 °F for nighttime temperatures. When daytime temperatures exceed 90 °F, photosynthetic capacity is reduced, and fewer sugars are produced. As overnight low temperatures increase, cellular respiration increases, requiring energy (sugars) that would otherwise be used to produce grain. Purdue University published a report that estimates about a 2% yield loss could occur in corn for every 1 °F increase in the average nighttime minimum temperature during July.6 Lower corn yields in Iowa in 2010, compared to record yields (for that time) in 2009 were attributed to warmer nighttime temperatures that occurred in 2010.7

Higher average minimum temperatures can directly impact the accumulation of growing degree days (GDD), potentially accelerating crop development while also reducing the time available for grain fill. Iowa State University reported that overnight lows between July 15 and August 15, 2010, recorded at five locations averaged about eight degrees warmer compared to the same locations in 2009. Based on simulated results, they concluded that the higher minimum nighttime temperatures in 2010 reduced the grain filling period by 6 to 13 days.7

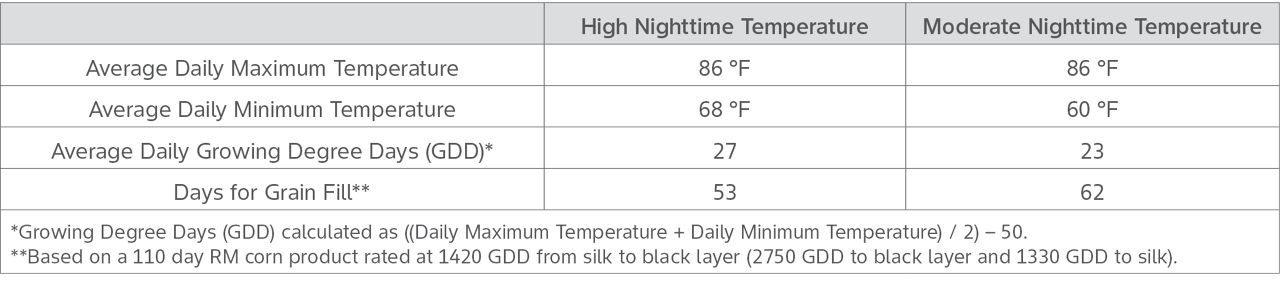

An illustration of how an average daily minimum temperatures of 68 °F, compared to an average of 60 °F, could potentially impact the rate of crop development during the critical grain fill period is shown in Table 1.

Table 1. The estimated effect of average high nighttime temperatures and moderate nighttime temperatures on growing degree day accumulation and days for grain fill in corn.

Kernel abortion can occur when successful pollination is followed by drought or heat stress and is usually more frequent at the ear tip. Drought or heat stress during the first two weeks after pollination is the most critical in determining if abortion may occur. Aborted or poorly filled kernels are small, shrunken and an off-white color. Kernel abortion may not always be the result of heat or drought stress as lack of nitrogen, excessive foliar disease reducing photosynthesis, or even several days without adequate sunshine can also contribute to kernel abortion.

Corn can be vulnerable to reductions in kernel weight through full maturity (R6 growth stage). The lack of photosynthate during the dough (R4) and dent (R5) growth stages can result in premature formation of the black layer, sometimes leading to higher grain moisture content and slower drydown. Stalk weakness or lodging can result from severe heat or drought stress as the plant moves resources from the stalk to developing kernels. Premature plant death can occur under severe drought or heat stress with yield losses likely greater when plant death occurs at growth stage R5 or earlier.1,8

Sources

1Lauer, J. 2018. What happens within the corn plant when drought occurs? University of Wisconsin-Madison Extension. https://dunn.extension.wisc.edu/files/2018/09/CV-Ag-News-Fall-2018-Page-2-Corn-plant-during-drought.pdf.

2Nielsen, R. Some of those corn plants are thirsty! Purdue University Extension. https://www.agry.purdue.edu/ext/corn/news/articles.96/p&c9633.htm.

3Abendroth, L., Elmore, R., Boyer, M. and Marlay, S. 2011. Corn growth and development. Iowa State University Extension and Outreach. https://shop.iastate.edu/extension/farm-environment/crops-and-soils/agronomic-crops/pmr1009.html

4Nielsen, R. Drought and Heat Stress Effects on Corn Pollination. Purdue University Extension. https://www.agry.purdue.edu/ext/corn/pubs/corn-07.htm.

5Hoegemeyer, T. 2011. How Extended High Heat Disrupts Corn Pollination. University of Nebraska. https://cropwatch.unl.edu/how-extended-high-heat-disrupts-corn-pollination-0.

6Bowling, L., Widhalm, M., Cherkauer, Kl, Beckerman, J., Brouder, S., Buzan, J., Doering, O., Dukes, J. S., Ebner, P., Frankenberger, J., Gramig, B., Kladivko, E., Lee, C., Volenec, J., and Weil, C. 2018. Indiana’s agriculture in a changing climate: A report from the Indiana Climate Change Impacts Assessment. Purdue Climate Change Research Center, Purdue University. West Lafayette, Indiana. https://ag.purdue.edu/indianaclimate/agriculture-report/

7Elmore, R. 2010. Reduced 2010 corn yield forecasts reflect warm temperatures between silking and dent. Iowa State University Extension and Outreach. https://crops.extension.iastate.edu/cropnews/2010/10/reduced-2010-corn-yield-forecasts-reflect-warm-temperatures-between-silking-and

8Nielsen, R. 2018. Effects of Severe Stress During Grain Filling in Corn. Purdue University Extension. https://www.agry.purdue.edu/ext/corn/news/timeless/GrainFillStress.html.

Web sources verified 5/7/2025. 1222_137271.

Disclaimer

Always read and follow pesticide label directions, insect resistance management requirements (where applicable), and grain marketing and all other stewardship practices.