5 MIN READ

Fall Application of Lime and Fertilizer

July 28, 2025

Soil Sampling

Regardless of when fertilizer or manure is applied, soil samples should be obtained to help verify the amounts of macro- and micronutrients to apply. Soil samples should be obtained at least every three to four years during the same time frame by using sampling techniques recommended by local University Extension offices. The analysis results should include the availability of macro- and micronutrients, pH, organic matter (OM), and cation exchange capacity (CEC). The CEC of a soil indicates how often a soil should be tested. If the CEC is high, the soil can hold cation nutrients longer and the pH is likely to be more constant; therefore, soil testing can be done less often. If the CEC is less than 7, cation nutrients may leach easily; therefore, testing should be more frequent.1 Soil sampling should be more frequent with continuous cropping systems such as continuous corn.

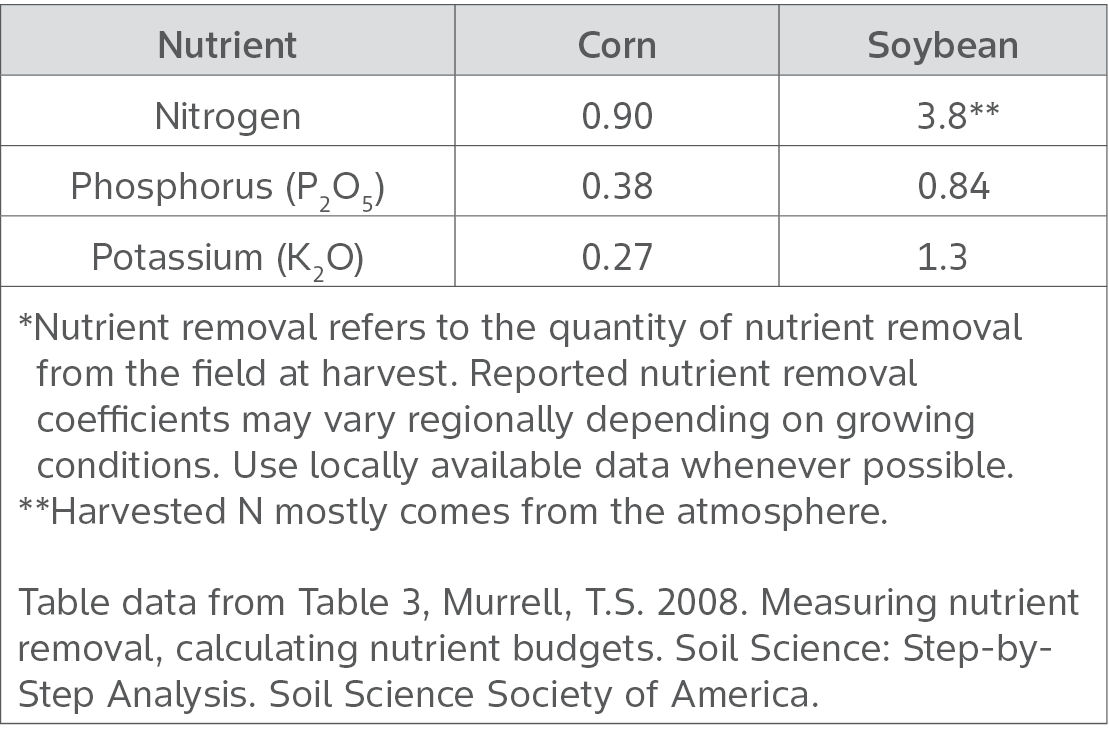

Generally, fall is the best time for soil sampling because soil moisture content may be low. If possible, fall is also the best time to apply any required lime. If fall sampling is not practical because of soil moisture, late harvest, workload, or other reasons, fall fertilizer recommendations can be based on samples collected the previous spring if the recently harvested crop’s nutrient removal is considered (Table 1).2,3 Nutrient removal by the crop varies depending on soil conditions, yields, seed product differences, and fertilizer rates. Soil tests can estimate the fertilizer quantity required based on crop yield.

Table 1. Nutrient removal (lb/bu) in corn and soybean.*

Sampling depth is important for nutrient evaluation because of stratification in conservation tillage systems and nutrient leaching. For phosphorus (P), potassium (K), pH, OM, soluble salts, zinc (Zn), iron (Fe), manganese (Mn), copper (Cu), and boron (B), a sampling depth of 0 to 6 inches is recommended. For mobile nutrients such as nitrate, chloride (Cl), and sulfur (S), a 24-inch sampling depth is recommended.4 Evaluating nutrient levels at several depths may be beneficial depending on the cropping system and crop to be grown. Recommendations for grid sampling may differ from larger sampling areas.

Lime Application

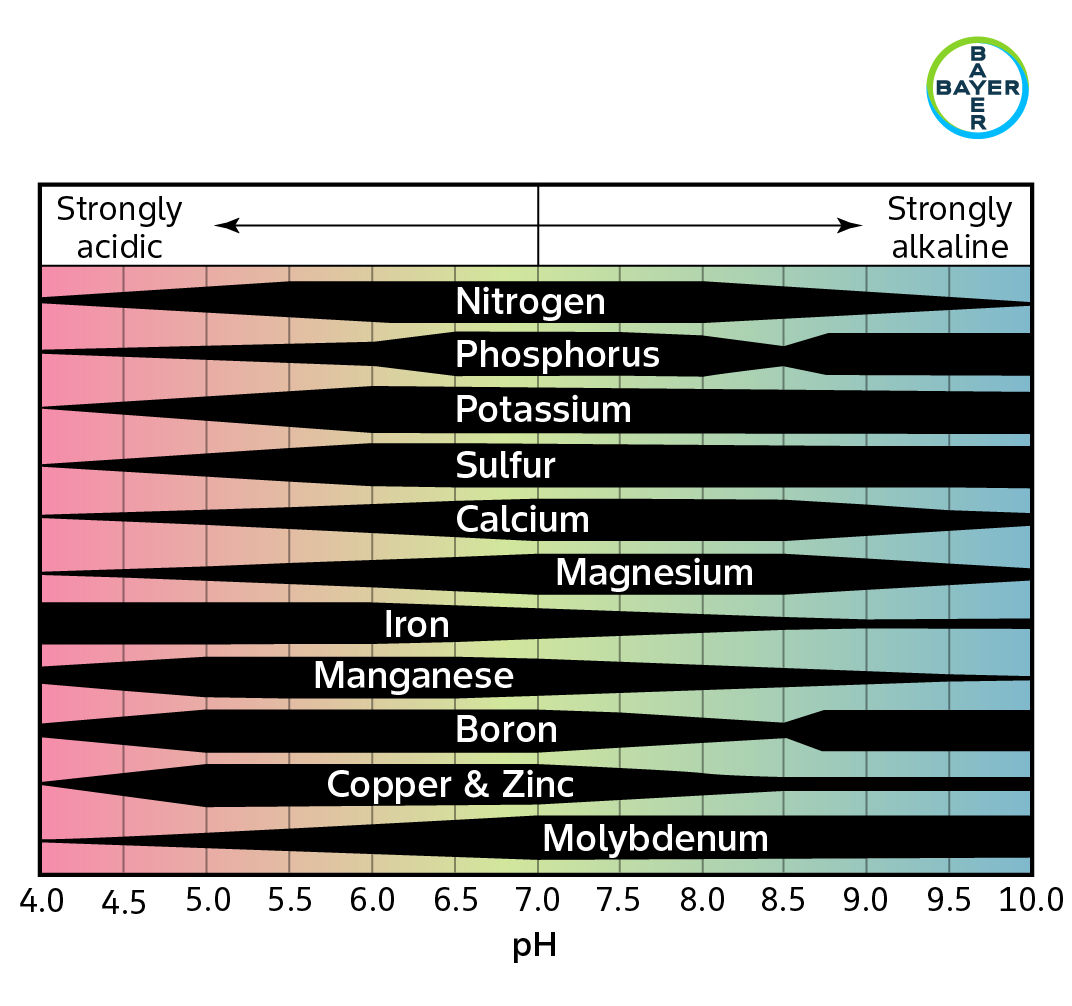

Lime is required to neutralize soil acidity by altering soil pH. Soil pH can range from 4.0 (strongly acid) to 10.0 (strongly alkaline) and nutrients become more or less available depending on pH (Figure 1). Nutrients are most available to plants when soil pH ranges between 6.0 and 7.0. Lime takes time to dissolve and neutralize acidity; therefore, it should be applied three to six months before planting crops. Additionally, different particle sizes from different lime sources dissolve at different rates and have different neutralizing efficiencies. Because lime can interfere with the availability of nutrients, especially P, lime should be applied and incorporated at least a month before applying other nutrients. Sources of lime include materials containing calcium (Ca) and/or magnesium (Mg) that are capable of neutralizing soil acidity, such as calcitic and dolomitic limestone, burnt lime, slaked lime, marl, and various by-products.

Phosphorus and Potassium

Phosphorus (P) and potassium (K) are typically applied in the fall because of the generally drier soils, their availability, farm workload, and the tillage requirement to help reduce their loss through erosion or runoff. Applications of P and K to frozen soils should be avoided because potential runoff can lead to algae blooms in lakes, streams, rivers, and the Gulf. Common P fertilizers include superphosphate, concentrated superphosphate (CSP), monoammonium phosphate (MAP), diammonium phosphate (DAP), and ammonium polyphosphate (APP). Common K fertilizers include potassium chloride, potassium sulfate, potassium-magnesium sulfate, potassium thiosulfate, and potassium nitrate.

In the soil, P is very immobile and held tightly by soil colloids. Crop roots must be able to reach P soil concentrations for uptake. Any stress that reduces root growth can result in plants showing P deficiency. Potassium is either available, slowly available, or readily available depending on the parent material holding the K and how quickly the parent material releases K through weathering. The amount of K leaching is generally low unless it becomes part of the soil solution and is leached.

To maintain soil P and K, it is common to apply P and K fertilizers on a two-year cycle of crop production, usually after a soybean crop, to maintain soil P and K fertility. This is particularly true for K, as a soybean crop requires a substantial amount of K. Corn residue, if not removed, can return approximately 60% of the K utilized by the plant during growth. Soil tests should be conducted to determine if P and K levels have dropped below maintenance levels, which would require higher application rates to restore adequate soil reserves.

Nitrogen Application

Reduced soil compaction, workload distribution, and economic incentives are advantages for applying nitrogen (N) in the fall. Disadvantages can include the loss of N between application and crop use and environmental concerns of nitrates leaching into streams, lakes, and groundwater.

Fertilizers comprised predominantly of ammonium-N are preferred for fall application. Nitrogen sources containing urea and/or nitrates have greater potential to be lost via leaching, volatilization, or runoff. Nitrate-N is subject to loss via leaching and denitrification while ammonium-N is relatively stable as it attaches to soil particles. Due to these concerns, anhydrous ammonia is a good source for fall-applied N.

Anhydrous ammonia should be applied in late fall after soil temperatures cool to 50 °F (10 °C) or less and cool weather is expected to continue (Figure 2). Generally, fall N applications are only feasible in areas where winter soil temperatures limit ammonium nitrification. It should not be applied in areas where soils seldom or never freeze or where there is a long period between the time soils reach 50 °F (10 °C) and when they freeze. Nitrifying organisms that convert ammonium to nitrates can continue to function at temperatures as low as 32 °F (0 °C); however, the rate of nitrification is reduced. Long periods at soil temperatures above 32 °F (0 °C) can still result in nitrification of a large percentage of the applied ammonium-N. The use of a nitrification inhibitor can slow the conversion of ammonium to nitrates and improve the effectiveness of fall-applied N. Avoiding fall N applications to sandy and poorly drained soils is a best management practice.

Splitting N applications between fall, spring, and sidedressing should be considered. Spring and sidedress applications may allow for increased efficiency of N utilization, particularly when growing conditions are wet and cool. The Corn Nitrogen Rate Calculator developed by Iowa State University in association with other Midwestern Universities is a tool that can help find the maximum return to N and the most profitable N rate.5

Manure Application

Manure can be an adequate nutrient source of N, P, K, and micronutrients. However, one application may not be optimal for all nutrients. The nutrient content of manure varies depending on livestock type, feed ration, and manure storage and handling. A manure nutrient analysis should be completed prior to application. Manure sources that have high inorganic ammonium content, such as liquid swine manure, should be applied in late fall after soils cool. For manure with considerable bedding, fall application can provide more time for microbial mineralization to inorganic N, which can increase N availability to the crop.6

Manure injection or incorporation should be considered to reduce potential N volatilization and P runoff. Manure applications to frozen soils, sloping soils, or to residue-free fields should be avoided. Cover crops can help retain N and P in no-till cropping systems. For additional manure application information, please visit Fertility from a Manure Perspective.

Sources

1Mengel, D.B. and Hawkins, S.E. Soil sampling for P, K, and lime recommendations. AY-281-W. Soil/Fertility. Agronomy Guide. Purdue University Cooperative Extension. https://www.extension.purdue.edu/extmedia/AY/AY-281.html

2Sawyer, J. and Mallarino, A. 2009. Getting ready for fall fertilization. Integrated Crop Management News. Iowa State University Extension and Outreach. https://crops.extension.iastate.edu/cropnews/2009/09/getting-ready-fall-fertilization/

3Murrell, T.S. 2008. Measuring nutrient removal, calculating nutrient budgets. In S. Logsdon, D. Clay, D. Moore, and T. Tsegaye (Eds.) Soil science: Step-by-step analysis. Soil Science Society of America. https://www.soils.org/files/certifications/certified/education/self-study/exam-pdfs/147.pdf

4Gelderman, R., Gerwing, J., Reitsma, K. 2006; Clark, J. 2019. Recommended soil sampling methods for South Dakota. South Dakota State University Extension. https://extension.sdstate.edu/sites/default/files/2019-09/P-00132.pdf.

5Corn nitrogen rate calculator. Iowa State University. https://www.cornnratecalc.org/

6Mallarino, A.P. and Sawyer, J.E. 2023. Using manure nutrients for crop production. Iowa State University Extension and Outreach. https://store.extension.iastate.edu/product/Using-Manure-Nutrients-for-Crop-Production

Additional Sources

Hoeft, R.G., Aldrich, S.R., Nafziger, E.D., Johnson, R.R. 2000. Modern corn and soybean production. Chapter 6. Nutrient management for top profit. pp. 107-171. MCSP Publications, Champaign, IL.

Ferguson, R.B., Hergert, G.W., Shapiro, C.A., and Wortmann, C.S. 2007. Guidelines for soil sampling. NebGuide. G1740. University of Nebraska-Lincoln. https://extensionpubs.unl.edu/publication/g1740/2007/pdf/view/g1740-2007.pdf

Culman, S., Zone, P.P., Kim, N., et al. 2019. Nutrients removed with harvested corn, soybean, and wheat grain in Ohio. ANR-74. Ohio State University Extension. Ohioline. The Ohio State University College of Food, Agricultural, and Environmental Sciences (CFAES). https://ohioline.osu.edu/factsheet/anr-74

Web sources verified 6/24/25. 1110_95272

Disclaimer

Always read and follow pesticide label directions, insect resistance management requirements (where applicable), and grain marketing and all other stewardship practices.