Anhydrous Ammonia Fall and Spring Applications

September 17, 2025

Across the Midwest, anhydrous ammonia (NH₃) remains a go-to nitrogen (N) source for farmers. With the rising cost of inputs and increasing pressure to farm sustainably, understanding how to safely and efficiently use anhydrous ammonia in fall and spring is more important than ever.

What is anhydrous ammonia? Understanding Its Properties

Anhydrous ammonia contains 82% nitrogen by weight and is a pressurized liquid that immediately converts into a gas upon injection into the soil.1 Once applied, it rapidly reacts with soil moisture to form ammonium (NH₄⁺), which is why NH₃ must be injected beneath the soil surface. In the soil, NH₃ diffuses outward from the injection point, typically forming a concentrated zone about 3 to 4 inches in diameter.2 This zone may be larger in sandy or excessively dry soils due to less moisture resistance. Anhydrous ammonia has a strong attraction for water, and when it reacts with soil moisture, it gains a hydrogen ion to become ammonium. Being positively charged, ammonium ions bind tightly to negatively charged soil particles, which prevents the ammonium from moving freely with water. Over time, soil bacteria convert ammonium to negatively charged nitrate (NO₃⁻) through a process known as nitrification.3 Because of its negative charge, nitrate is not bound to soil particles, which allows it to be mobile in the soil solution. This mobility increases the risk of nitrogen loss through leaching, movement beyond the root zone with water, or denitrification, a microbial process in saturated soils that transforms nitrate into gaseous forms of nitrogen, which then can escape into the atmosphere. Compared to other nitrogen fertilizers, NH₃ converts to nitrate more slowly, reducing the immediate risk of nitrogen loss. However, warm temperatures and wet soil conditions can accelerate this conversion process.

Fall vs. Spring Application of Anhydrous Ammonia

Anhydrous ammonia is preferred for fall applications because it converts to nitrate more slowly than other nitrogen (N) forms, reducing the potential for early-season N loss. When applied correctly, fall N can spread out labor demands, reduce spring soil compaction, lower input costs, and help ensure N is available if spring soil conditions delay field work, including fertilizer applications. However, fall applications do carry an increased risk of N loss through leaching or denitrification, especially when wet late-winter or spring conditions are warm and wet.3,4,5

Spring anhydrous applications place N closer to the time of plant uptake, reducing risk of N losses from leaching, denitrification, or volatilization occurring when fall-applied N is left unused through winter and early spring. This timing helps improve N use efficiency and can result in more consistent crop performance, especially in fields with high water tables, sandy soils, or poor drainage. Additionally, spring-applied anhydrous avoids the uncertainty of fall weather conditions, which can lead to unpredictable N transformations in the soil. However, spring anhydrous ammonia applications are not without risks. It can create tight planting windows and increase soil compaction if applied under wet field conditions. Equipment limitations and time constraints during a busy spring season may also delay planting or reduce application accuracy. In some years, wet weather in early spring may prevent timely N application altogether, potentially compromising early corn growth. For these reasons, while applying anhydrous ammonia in the spring is generally more agronomically efficient, it requires careful planning to balance logistical challenges and weather risks.1,6

Anhydrous Ammonia and Soil Characteristics

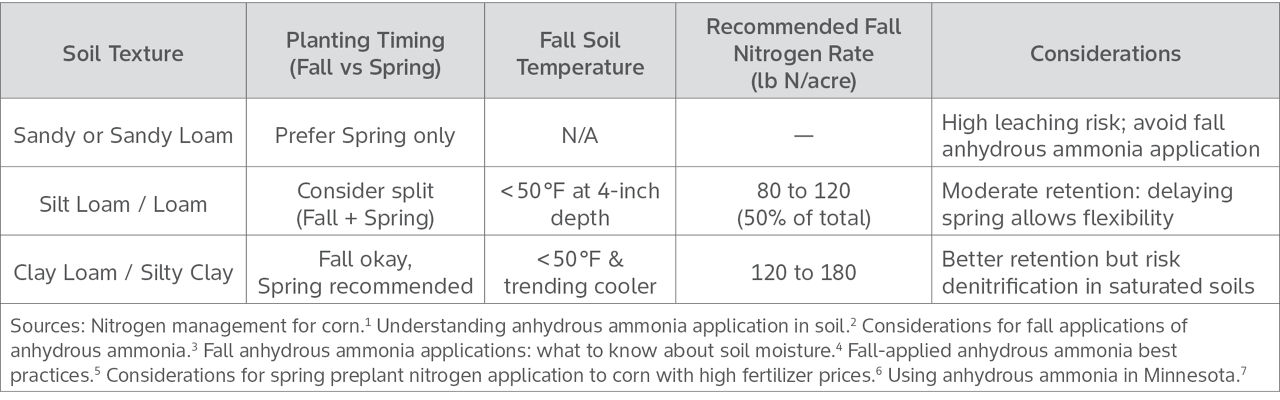

Fall anhydrous ammonia applications to soils that are sandy, easily drained, have a high pH, or poorly drained should be avoided due to their increased risk for N loss. Applying N in these environments can lead to lower fertilizer efficiency and greater environmental harm. For these reasons, many experts recommend limiting fall applications to only a portion of planned corn acres or considering a split-application strategy. Applying a portion of N in the fall and the remainder in the spring can help increase N use efficiency and help reduce the risk of N loss if spring conditions become wet.4,5

The Corn Nitrogen Rate Calculator is a very useful tool to help determine N rates based on past field response and estimated N cost.

Application rates depend on:

- Soil type: Clay soils can retain ammonium better, while sandy soils are prone to leaching.

- Expected yield potential: Use yield-based nitrogen calculators. A common rule: 0.8 to 1.0 lb N per expected bushel of corn.1

- Residual soil nitrate levels: Adjust rates based on pre-plant nitrate tests.

Table 1. Anhydrous ammonia application considerations

Anhydrous Ammonia Application Timing and Depth

To help mitigate N loss and stable conversion of anhydrous ammonia to ammonium in the fall, it should only be applied after soil temperatures have dropped below 50 °F at a 4-inch depth and are expected to remain cool.6 Using nitrification inhibitors alongside ammonia can further slow the conversion of ammonium to nitrate, providing more time for the plant to access the N in the spring. Proper soil conditions, as stated above, are also key and soil should be moist, not overly wet or dry for anhydrous ammonia applications. Anhydrous should be injected 6 to 8 inches deep.3 Wet soils may not seal properly after injection, leading to volatilization losses, while dry, cloddy soils can allow ammonia gas to escape through soil cracks. In drier conditions, anhydrous ammonia should be injected at least eight inches deep to help reduce ammonia loss.

Spring anhydrous ammonia applications should be applied as early as soil conditions allow. To help avoid potential seed and/or seedling injury applications should be one to two weeks before planting and injected on an angle relative to row direction.7 If planting occurs too early after the anhydrous application and the corn rows are parallel to and on the same spacing as the application knives, there is an increased potential for seed or seedling injury if seed is planted within the knife slot.

Anhydrous Ammonia Precautions for Safe Use

Anhydrous ammonia can cause severe burns or respiratory damage with direct exposure. Proper handling and training are critical.8

- Always wear protective goggles, gloves, and long sleeves

- Check hoses and fittings for leaks

- Never leave tanks pressurized when not in use

- Be prepared with a water supply and emergency protocol

For additional anhydrous ammonia safety information, please see Iowa State Publication Safety First with Anhydrous Ammonia Applications.

For tailored anhydrous ammonia local recommendations, consult with your Channel® Brand Technical Agronomist. Responsible use of NH₃ not only supports your crop goals but also safeguards our shared soil and water resources.

Channel Agronomist

Joel DuPre

Sources

1Nafziger, E.D. Chapter 9: Nitrogen management for corn. Illinois Agronomy Handbook. University of Illinois Extension, Department of Crop Sciences. https://extension.illinois.edu/sites/default/files/iah_-_nitrogen_management_for_corn_v4.pdf

2Sawyer, J. 2019. Understanding anhydrous ammonia application in soil. ICM News. Integrated Crop Management. Iowa State University Extension and Outreach. https://crops.extension.iastate.edu/cropnews/2019/03/understanding-anhydrous-ammonia-application-soil

3Diaz, D.R., and Knapp, M. 2020. Considerations for fall applications of anhydrous ammonia. Agronomy eUpdates. Issue 824. Kansas State University. https://eupdate.agronomy.ksu.edu/article_new/considerations-for-fall-applications-of-anhydrous-ammonia-412-3

4Roth, R.T. and Wuestenberg, M. 2024. Fall anhydrous ammonia applications: what to know about soil moisture. Blog. Integrated Crop Management. Iowa State University Extension and Outreach. https://crops.extension.iastate.edu/post/fall-anhydrous-ammonia-applications-what-know-about-soil-moisture

5Camberato, J. 2021. Fall-applied anhydrous ammonia best practices. Soil Fertility Update. Purdue University Department of Agronomy. https://ag.purdue.edu/news/department/agry/kernel-news/2021/10/_docs/fall-anhydrous-oct-2021.pdf

6Mallarino, A. 2022. Considerations for spring preplant nitrogen application to corn with high fertilizer prices. ICM News. Integrated Crop Management. Iowa State University Extension and Outreach.

https://crops.extension.iastate.edu/cropnews/2022/04/considerations-spring-preplant-nitrogen-application-corn-high-fertilizer-prices

7Overdahl, C.J. and Rehm, G.W. 1990. Using anhydrous ammonia in Minnesota. University of Minnesota. AG-FO-3073. https://conservancy.umn.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/023c3ddb-f430-463b-898e-b61230ad699e/content

8Rieck-Hinz, A. and Michel, J. 2022. Safety first with anhydrous ammonia applications. Blog. Integrated Crop Management. Iowa State University Extension and Outreach. https://crops.extension.iastate.edu/post/safety-first-anhydrous-ammonia-applications

Other sources

Sawyer, J. 2013. Corn nitrogen rate calculator. ICM News. Integrated Crop Management. Iowa State University Extension and Outreach. https://crops.extension.iastate.edu/cropnews/2013/06/corn-nitrogen-rate-calculator-update

Web sites verified 7/28/25. 1110_624704

Disclaimer

Always read and follow pesticide label directions, insect resistance management requirements (where applicable), and grain marketing and all other stewardship practices.