Manure Applications and the Potential for Nitrogen Loss

January 3, 2025

The fall of 2024 was unusually warm throughout the Corn Belt which resulted in manure applications being applied well before soils had cooled below the 50 °F target for fall nitrogen applications. That decision, while not ideal can sometimes be unavoidable. With manure pits filling, they had to be emptied. Normally, soils in the upper Corn Belt are fit for a nitrogen (N) application around mid to late-October. Data from the Iowa Environmental Mesonet at Iowa State University showed that the average 4-inch soil depth temperatures didn’t get under 50 °F until mid-November.1 Since liquid manure applications are generally knifed in at a depth of 6- to 8-inches where the soil temperature is warmer, N loss would likely occur.

Nitrogen in manure is in two forms, ammonia NH4+ and organic N which is found in the organic matter. Ammonia is positively charged and loosely binds to the negatively charged soil particles. That binding helps keep soil N stable if it stays in the ammonia form. However, with soils above 50 °F, autotroph bacteria attempt to steal electrons from the ammonia and cause the N to chemically rebalance. The ammonia drops its hydrogen and pairs up with oxygen instead and transitions to nitrite (NO2-) and then to nitrate (NO3-). As indicated by the chemical signals, the N compounds have switched to a negatively charged compound which causes the N to be repelled from the soil particles like two magnets repel each other. Nitrate dissolves in water very easily and with the active weather much of the Corn Belt experienced in November some of the N could have leached and washed away. Products like nitrapryin can slow down the nitrification process by controlling the population of some of the microbes; however, they cannot stop the process. How long soils are above 50 °F plays a key role in how much NH4+ is converted to NO2- and NO3-. An uncontrolled autotroph population can complete the nitrification process in about two to three weeks.3 That means manure applied in October could be completely converted before mid-November.

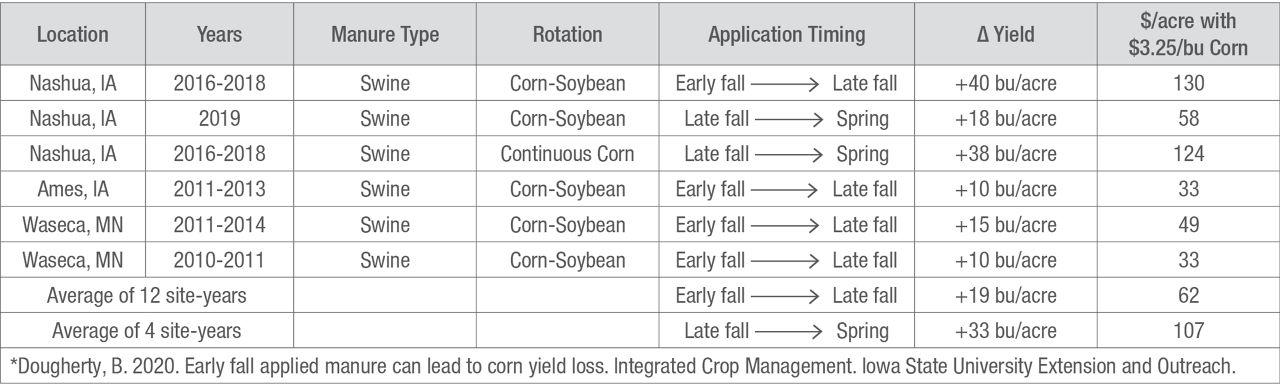

An Iowa State University research trial conducted from 2016 through 2018 at various sites found corn yield was reduced by an average of 19 bu/acre when manure was applied with soil temperatures exceeding 50 °F and manure was the main N source for corn.2 Similarly, in 2019 they tested late fall to spring applied manure and found an average 18 bu/acre yield advantage if the manure was applied in the spring (Table 1).2

Table 1. Corn yield and gross revenue advantage with delayed manure application assuming a corn price of $3.25/bu.*

What should be done when manure has been spread? Most importantly, don’t guess how much N has been lost, test and find out. In random field locations, take four to five 12-inch soil cores in each spot by starting in the row and moving across the row. This is the best way to determine the available N for plant use and can help determine the amount of sidedress needed for your corn. Tissue sampling in the spring can also be an effective way to determine what N is available in the plant. Also, the water coming out of tile lines can be tested for nitrate. Reported values are likely to be in parts per million (PPM). To convert PPM to pounds per gallon (PPG), multiply the PPM x 8.33588 x 10-8. If needed, there are several online conversion sites that can help with conversions. The first flush from the tile line is the heaviest for nitrate and goes down from there. Because of the variation, sampling multiple times is necessary for accuracy. The flow rate for the size of tile is also required for the calculations. To help with this, several flow rate calculators are online. This lets one know what has been lost; however, it may not be a good indicator of what is still in the soil. For that, compare the loss value to application rates and manure quality tests. In any case, assume some amount of N has been lost if manure was applied prior to soils getting below 50 °F and more N may be necessary for a plentiful 2025 crop.

Channel Agronomist

Lucas Gillmore

Sources

1Iowa Environmental Mesonet. Iowa State University. https://mesonet.agron.iastate.edu/

2Dougherty, B. 2020. Early fall applied manure can lead to corn yield loss. Integrated Crop Management. Iowa State University Extension and Outreach. https://crops.extension.iastate.edu/blog/brian-dougherty/early-fall-applied-manure-can-lead-corn-yield-loss

Additional Source

Nelson, D.W. and Huber, D. Nitrification inhibitors for corn production. Crop Fertilization. NCH-55. National Corn Handbook. Iowa State University.

Web sites verified 11/22/24 1110_487802

Disclaimer

Always read and follow pesticide label directions, insect resistance management requirements (where applicable), and grain marketing and all other stewardship practices.