Benefits of Using a Fungicide on Corn in the South

May 9, 2025

KEY POINTS

- Maintaining yield potential through protecting the leaf surface area from foliar disease and increasing late-season plant staygreen which is especially important for corn harvested as silage.

- Understanding which diseases are fungal and can benefit from a fungicide application, and which diseases are bacterial and not controlled by a fungicide.

- Corn planting dates can affect the potential for yield loss due to foliar diseases. Later planted corn may have more fungal disease pressure at an earlier growth stage and a greater yield response to a properly timed fungicide application than an earlier planted corn crop.

Introduction

Corn is a major crop in the South and growers include several control methods to help protect corn from diseases. One effective strategy is early planting which allows growers to align crop development with potential disease pressure. Additionally, the application of fungicides plays a crucial role in both helping to prevent and treating corn diseases. Successful management begins with an understanding of the field's disease history and involves regular scouting to monitor and control any emerging threats

Southern Corn Diseases

There are several economically important corn leaf diseases in the South that can benefit from fungicide use, including:

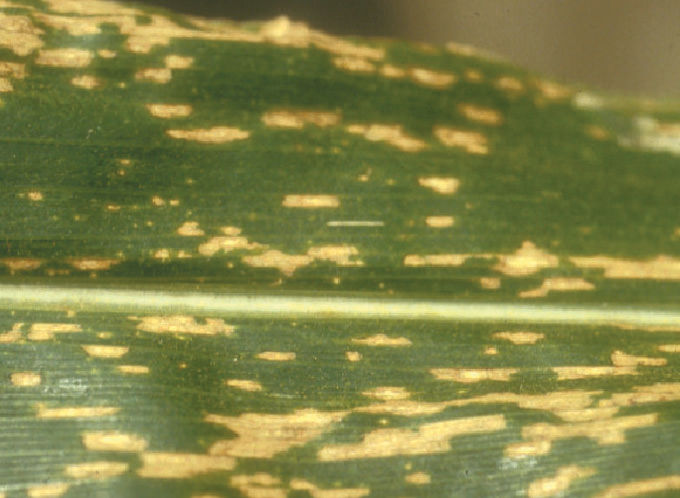

- Gray leaf spot (Figure 1)

- Northern corn leaf blight (Figure 2)

- Southern corn leaf blight (Figure 3)

- Tar spot (Figure 4)

- Anthracnose leaf blight (Figure 5)

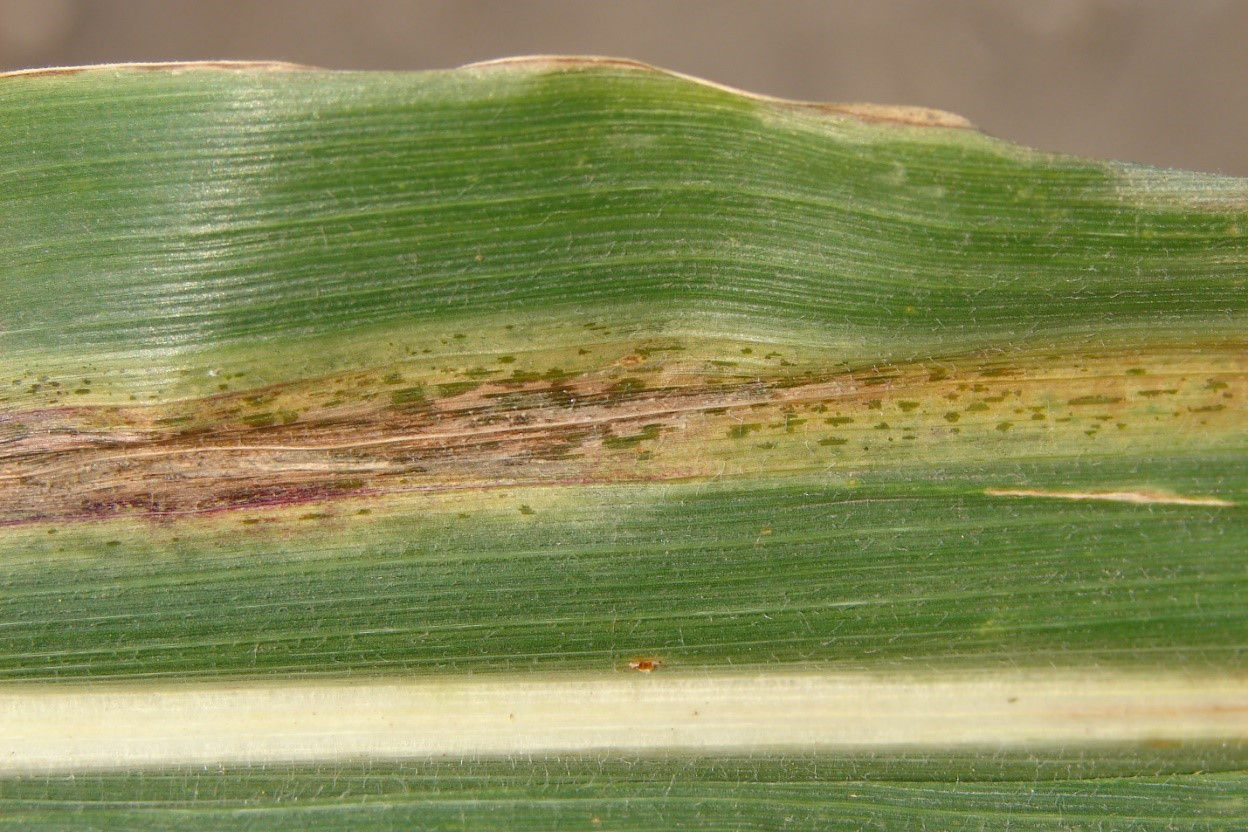

- Southern rust (Figure 6)

- Common rust (Figure 7)

- Eyespot (Figure 8)

- Northern corn leaf spot (Figure 9)

However, there are also bacterial corn diseases that are not controlled by a fungicide application, which include:

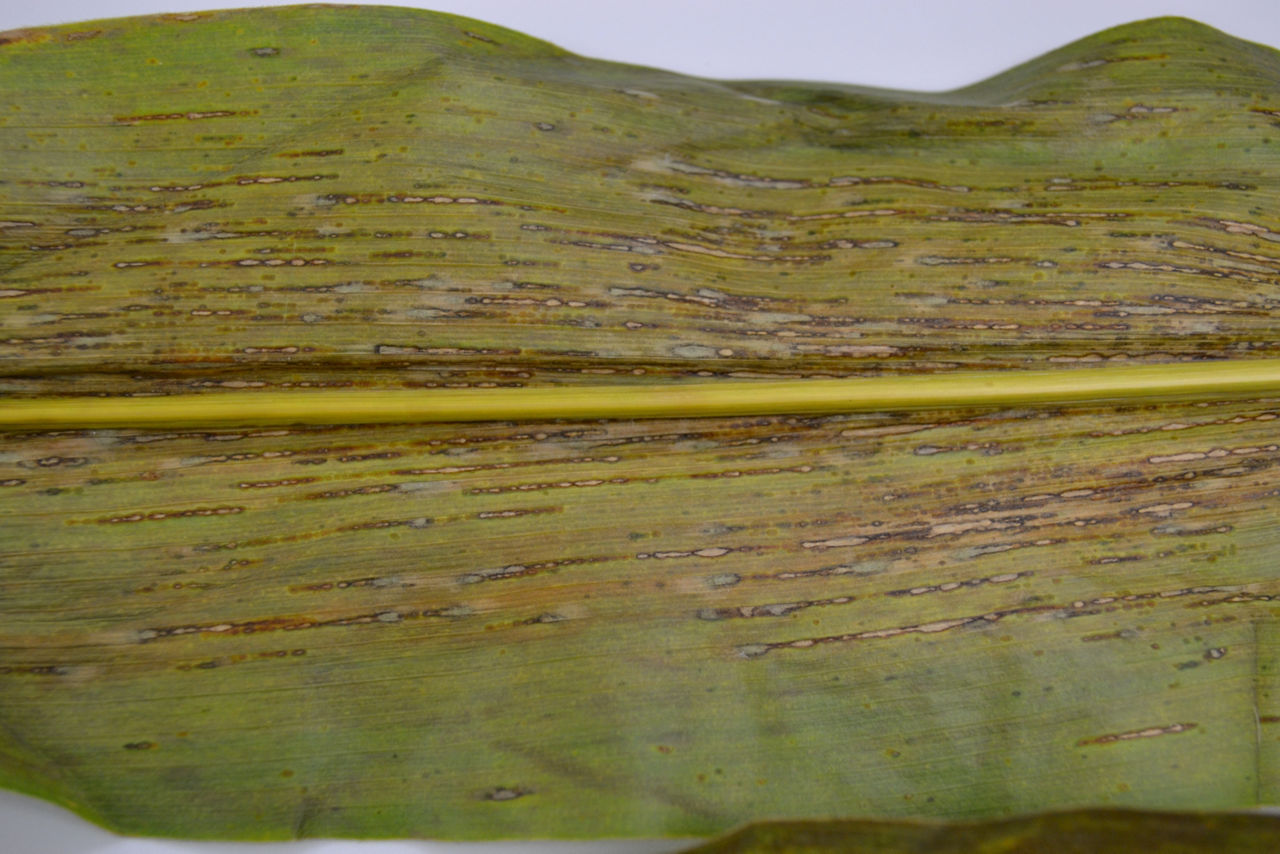

- Bacterial leaf streak (Figure 10)

- Stewart’s wilt (Figure 11)

- Goss’s wilt (Figure 12)

Scouting Program

Scouting corn through the grain fill (R4) growth stage can help identify which diseases are developing during the growing season and if a disease has reached the control level for a fungicide application. The designated threshold for a fungicide application is dependent on the level of infection needed to reach a control level that has been established for the crop at each growth stage. Land-grant universities develop control levels for common fungal diseases that impact their state, that when followed, provide the best return on investment potential for the fungicide application.

The Crop Protection Network, created by land-grant universities, offers valuable resources for monitoring the progression of corn diseases throughout the United States. During the growing season, the network publishes weekly disease maps that highlight the locations where diseases have been detected and the rate at which they are spreading across the country.

Control Strategies

Cultural Practices for Controlling Fungal Corn Leaf Diseases

There are many cultural practices that can help mitigate corn leaf disease development, including:

- Selecting corn products that exhibit disease resistance.

- Planting early, from late February to April, to help ensure the crop reaches a later reproductive growth stage (R4) before fungal disease pressure necessitates a fungicide application to help safeguard yield potential.

- Implementing tillage practices to decrease plant residue from previous corn crops, which can harbor diseases from year to year.

- Rotating to a non-host crop to disrupt the disease cycle.

- Managing irrigation by minimizing the frequency and duration of irrigation to reduce leaf wetness.

Proactive Fungicide Control

In corn growing regions with a history of foliar disease pressure, implementing a proactive fungicide control program is often the most effective treatment strategy. Fungicides are generally most effective when used as protectants; therefore, applying them before disease infection occurs can greatly enhance the plant's defense against potential diseases. This proactive approach not only helps to safeguard the crop but also helps maintain overall yield potential.

Applying fungicides proactively may be beneficial for several reasons:

- Helping to protect the plant from disease development before symptoms appear. Some diseases like gray leaf spot (GLS) and tar spot have latency periods between the time of initial infection and symptom appearance. This allows time for a pathogen to invade plant cells and limit yield potential. Gray leaf spot has a two-week latent period from infection to visible lesions.1 There is also a latent period for tar spot which has been determined to be 14 to 20 days after infection, before visible symptoms of the disease appear on the leaf surface.2

- Reducing the impact of stress events such as disease, hail, drought, and heat. Plants under stress produce the ripening gas hormone ethylene. When ethylene is produced prematurely, plant growth slows, leaf senescence begins, and kernel abortion can occur, which negatively impacts yield potential. Fungicides that contain a strobilurin (Group 11) component inhibit the production of ethylene, which along with other effects, helps keep the plant growing in times of stress, such as drought.

- Helping to provide a barrier for leaves during periods of rapid growth, when the waxy layers on younger leaf surfaces become thinner and can allow an easier entry for disease into leaf tissue.1

For more information, please read: How do fungicides help reduce disease pressure in corn?

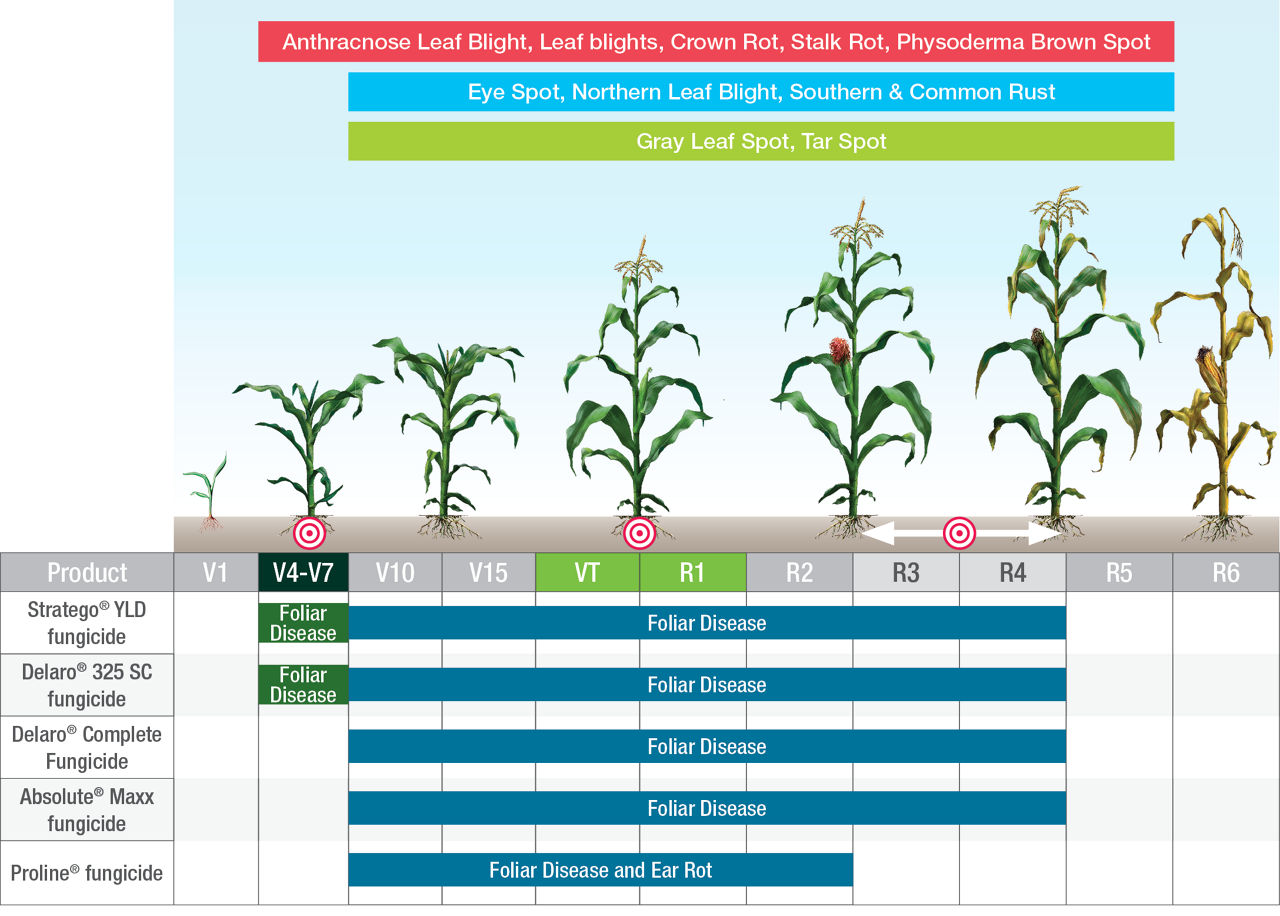

Fungicide Application Options

Fungicide product selection is important to help ensure control of the disease or combination of diseases that can affect the crop. Delaro® 325 SC Fungicide is labeled for control of gray leaf spot, northern corn leaf blight, southern corn leaf blight, tar spot, rust, eyespot, and anthracnose leaf blight.

Delaro® 325 SC Fungicide features a dual mode of action, combining trifloxystrobin (Group 11) and prothioconazole (Group 3). This formulation effectively targets rust diseases, which are prevalent in the southern regions. However, research indicates that applying fungicides after the dent stage (R4) of corn growth is not economically viable. This is particularly true for southern rust, one of the most challenging fungal diseases faced in the South.

Southern rust survives in tropical regions where spores are carried by the wind into southern U.S. corn growing areas landing on healthy corn. The spread of rust spores to other plants occurs only when conditions are favorable for disease development, allowing the rust fungus to proliferate and become a significant problem. Delaro® 325 SC Fungicide should be applied at a rate of 4 to 12 fl. oz. per acre, depending on plant growth stage and the target disease, and at a minimum of 2 gallons per acre (GPA) aerially or 10 GPA with ground applicators. Chemigation is approved for application through a center pivot, solid set, hand move, or moving wheel systems. Before an irrigation system can be used for a chemigation application, all functional check vales, vacuum relief valves, and low pressure drain valves, including all safety equipment required by the state where the application is being made, must be installed, and working on the irrigation system. For more information on Delaro® 325 SC Fungicide, go to https://www.cropscience.bayer.us/d/delaro-325-sc-fungicide.

Foliar disease pressure in Georgia and Alabama can be different than the Carolinas, but again the rust diseases are often the most problematic for corn production. A fungicide program that includes Absolute® Maxx fungicide may have a better fit for peanut growing areas. Absolute® Maxx fungicide contains two modes of action that includes trifloxystrobin (Group 11) and tebuconazole (Group 3) and efficiently controls the major fungal diseases of anthracnose leaf blight, rust, eye spot, gray leaf spot, northern corn leaf blight, northern corn spot, and southern corn leaf blight. Absolute® Maxx fungicide is not labeled for tar spot. The application rate for Absolute® Maxx fungicide is 5 to 6 fl. oz. per acre at a minimum of 2 GPA aerially or 10 GPA with ground applicators. As with Delaro® 325 SC fungicide, chemigation is also only approved for application through a center pivot, solid set, hand move, or moving wheel systems and all functional check vales, vacuum relief valves, low pressure drain valves, including all safety equipment required by the state where the application is being made, must be installed, and working on the irrigation system. For more information about Absolute® Maxx fungicide go to https://www.cropscience.bayer.us/d/absolute-maxx-fungicide. Always read and follow the label for states that have been approved for use, pre-harvest intervals restrictions, and all label instructions.

Sources:

12023. How do fungicides help to reduce disease pressure in corn? Bayer Crop Science. https://www.cropscience.bayer.us/articles/bayer/fungicides-in-corn-how-they-reduce-disease-pressure-and-when-to-apply.

2Valle-Torres, J., Ross, T. J., Plewa, D., et al. 2020. Tar spot: An understudied disease threatening corn production in the Americas. The American Phytopathological Society. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-02-20-0449-FE.

Web sites verified 02/13/2025. 1226_509000

Disclaimer

Always read and follow pesticide label directions, insect resistance management requirements (where applicable), and grain marketing and all other stewardship practices.